Anthony Cudahy (b. 1989) is a Brooklyn artist who paints from found photographs, movie stills, billboard posters, and queer archival iconography. He was recently featured in MAMOTH's group show ‘If On A Winter’s Night A Traveller’. In this interview, Cudahy elaborates on the meanings and processes behind a number of his featured works and tells us about his most recent work that he is undertaking during the quarantine. The figures in Anthony’s paintings seem to be captured moments of photography. The close-up face, the illuminated body, between the interlaced blocks of colour, the contrast between the light and shade like flash and projection, all link together the ambiance of the painting.

Installation view of ‘Eternity/bell-ringers’ @ Anthony Cudahy. Courtesy of MAMOTH

Installation view of ‘Eternity/bell-ringers’ @ Anthony Cudahy. Courtesy of MAMOTH

Anthony loves the hounds in Frans Snyder's’ sixteenth-century painting of the hunt, which is the archetypal reference for his Three Dogs. He sees Snyder’s dogs as the incarnation of dread, the essence of violence. In Cudahy’s painting, the ghost dog stretched over the figure might be there, or it might not. The painting’s window divides the inner and outer worlds. When Anthony converted this particular image into painting form, the hunting dog underwent a transformation. There was some level of conflict and uncertainty that arose between the painting and the image, which is both iterations as well as interpretation. The light falls away, the shadow embeds in the wall, and fear moves into nothingness.

Three Dogs, 2019, oil and acrylic on canvas, 121.9 × 152.4 cm @ Anthony Cudahy. Courtesy of MAMOTH

Three Dogs, 2019, oil and acrylic on canvas, 121.9 × 152.4 cm @ Anthony Cudahy. Courtesy of MAMOTH

MAMOTH: We noticed that there are always dogs that appear in your paintings, do they have some specific meaning to you?

A. Cudahy: Dogs are in a lot of my paintings, but I feel like I’m quoting a few different meanings for them. I love Snyder's dog on the hunt paintings from the 1600s. That’s where the dogs in the Three Dogs painting are quoted from. To me, these are shorthand for a feeling of terror or dread, the violence intrinsic in nature. In that painting, the ghost dog that’s stretched over him might be there or not, and there’s an inside/outside dichotomy with the picture window. Otherwise, when my own dog is in my paintings (not the MAMOTH ones), it’s more about domesticity or the family. In the Eternity painting, the dog figures are taken from medieval sarcophagi, so fidelity or waiting. They would be sculpted at the feet of the figure who died.

In the Gape paintings, a light source is hidden; and the face changes as the light does, from light to dark. It is as if the figure is fixed in position and day becomes night. The flowers become mystical, glowing in the night. The flowers face towards sunlight, and become their own light source. The face is moved and embedded in the wall of time.

(Left) Gape-Day, 2019, oil and acrylic on canvas, 50.8 × 40.6 cm (Right) Gape-Night, 2019, oil and acrylic on canvas, 50.8 × 40.6 cm @ Anthony Cudahy. Courtesy of MAMOTH

(Left) Gape-Day, 2019, oil and acrylic on canvas, 50.8 × 40.6 cm (Right) Gape-Night, 2019, oil and acrylic on canvas, 50.8 × 40.6 cm @ Anthony Cudahy. Courtesy of MAMOTH

MAMOTH: As for the Gape (Day/Night) paintings, are there any particular meanings behind those flowers?

A. Cudahy: The flowers in those paintings, I wanted it to become mystical at night and glow. As if the figure was fixed in position and the day became night. I like the idea of the flower going towards the sunlight, and then being its own source of light later.

MAMOTH: In most of the paintings, we can see colours infused into one another; the palette is blurred yet saturated with contrast; How did the aesthetic approach come to be?

A. Cudahy: I’ve long been interested in sort of a phosphorescent colour palette. Glowing colours next to dark ones. Lately, especially in the paintings at MAMOTH I was trying to make the colour relationships much more complex and not isolated into areas of one colour. So now they bleed into each other, hopefully in a deeper complex way.

In an interview, Anthony explained, “I've always been drawn to photography, and the visual language inherent to it. A cast shadow, or a pixelated degradation. I don't necessarily see it as opposed to a painting practice, but instead, as more visual language I can reference in my work.” When painting is infused with the visual language of photography, it changes the perspective. Gape-Day’s palette is minimized to the point that many details merge or become ambiguous, creating the glowing areas in the painting. Once the whole painting is saturated, gradually it becomes denser to the viewer, with areas of shimmering phosphorescence. In Gape-Night, the contrast between light and shadow brings a certain openness to the painting, expanding the scene. In Duo Swim, the characters are eternally gazing at something and seem to be playing the role of "caretaker": being queer does not belong to any differentiated group within the norms of society, but rather is independent and mutually supportive within, while still maintaining vigilance and holding feelings of insecurity towards the outside world. Anthony’s work reflects the duality of the queer environment in contemporary society.

Duo Swim, 2019, oil on canvas, 96.5 × 81.3 cm @ Anthony Cudahy. Courtesy of MAMOTH

Duo Swim, 2019, oil on canvas, 96.5 × 81.3 cm @ Anthony Cudahy. Courtesy of MAMOTH

MAMOTH: The work of Duo Swim evokes a parallel moment as if in a film: the characters are searching for something but seem like they don’t know what. Can you talk about the work?

A. Cudahy: In Duo Swim, I thought about the figures as ships or islands themselves, circling around each other. I think there’s something protective, in that one figure can see what the other can’t. I feel like the water became more solid as I painted it though, almost like they are in quicksand. It’s a painting that changes every time I look at it.

Anthony is also an avid image collector. Each image is filled with an aspect of his tenderness. Some originate from his family archive, some consist of random pictures taken from the Internet, and others from different artists' paintings, especially from the queer archive. He was astonished to discover that his mother’s uncle was gay and owned an antique shop in Manhattan in the 1970s. Anthony had never heard any stories about his uncle, nor his uncle's partner. Still, this family character has played a significant role in his personal narrative. The house his uncle lived in on Fire Island; and a copy of a cheque written to him by a famous actress, were all that Anthony could find in his family research. This search was very similar to the experience of flipping through an archive. He was looking for something unknown and uncertain that made him feel the need to make sense of things.

MAMOTH: When collecting images, how did you select them from archives? What are you trying to achieve with these images?

A. Cudahy: I have assembled my own archive over the years, collecting images and looking at them and reusing them over a decade now. These are from all over the place. From paintings throughout history, to screenshots on the internet, from news images to vernacular photography. I also utilize specific archives. Last year, my husband Ian and I were utilizing the physical archive at the Gay and Lesbian Center here in NYC. I’ve also used the ONE Archives online. I found Pat Rocco’s collection on there a few years ago and did several paintings of some of his group scenes. I don’t set out looking for a subject to paint, I just look and collect over time. When I see it, I know it. I can’t plan that much beforehand. There’s a spark, or a moment of an image gives me a colour idea, or a mood I want to explore. The quiet process of going down rabbit holes is a piece of my overall practice.

The past is not static. For Anthony, reflecting on the past is full of potential, and a process of discovering emerging truth. He studied and formulated an archive of image history, then revisited, reflected, imagined, and expanded it through painting. Gradually, marginalized groups are ignored or intentionally weakened. He created a cycle, an eternal place of return and reciprocation.

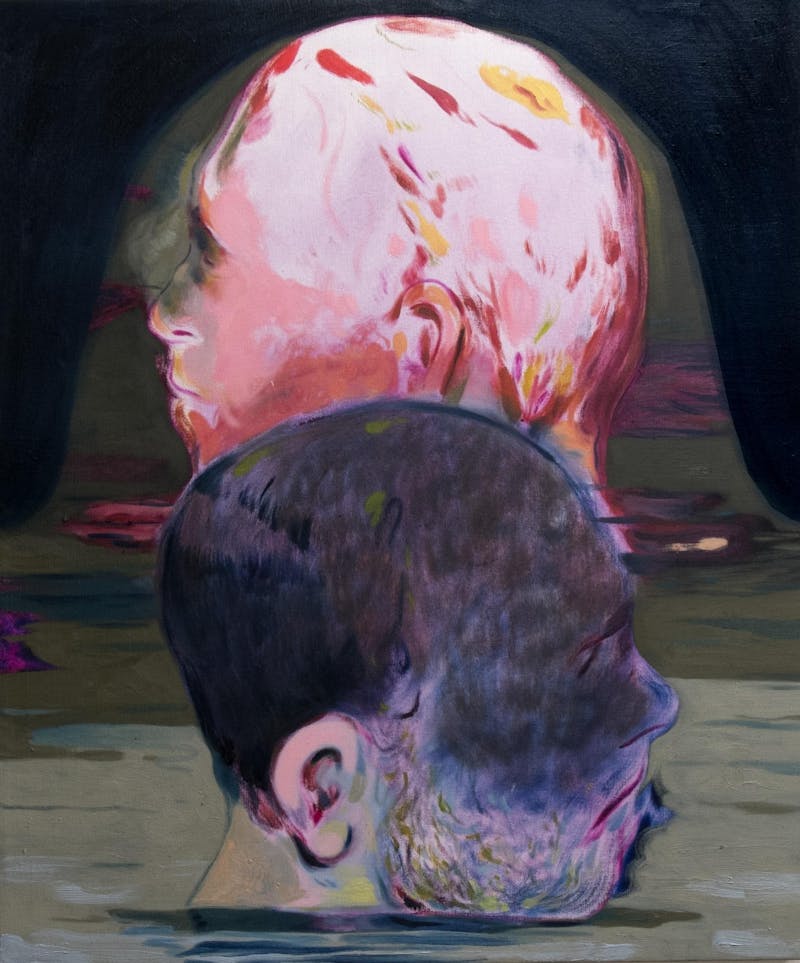

Eternity/bell-ringers, 2019, oil and acrylic on canvas, 243.8 × 152.4 cm @ Anthony Cudahy. Courtesy of MAMOTH

Eternity/bell-ringers, 2019, oil and acrylic on canvas, 243.8 × 152.4 cm @ Anthony Cudahy. Courtesy of MAMOTH

Eternity, takes shape between two bell ringers, between the strength of a man gazing into the distance and a man raising his arm on the verge of the ceremony of ringing. Inside the wall is shrouded light, outside the wall is endless distance.

MAMOTH: What is the process and the story behind Eternity/bell-ringers?

A. Cudahy: I was thinking of Panda Bear’s Person Pitch, an extreme piece of nostalgia for me, and how on that album every few seconds he lifts a curtain or releases pressure, and suddenly the listener realizes we’ve been underwater or in a different room than the sound. This suggests a subjectivity to the work; that there isn’t one way only to enter. After a summer of moving the figures around, and layering and removing paint, the two ended up as bell-ringers in eternity, forever pulling at an endless rope. Before them, demarcated by a thin line is another mystical world. Behind them, through a corridor, is a more earthly lighting and architectural situation. The first images collected to collage into this image were the sculptural dogs pieced together from several medieval sarcophagi with dogs in stone by their owners’ feet, forever on guard, waiting...

MAMOTH: Back to MAMOTH’s first group show last month, how do you feel about coming to London and attending MAMOTH’s exhibition opening?

A. Cudahy: The opening at MAMOTH feels like a different world, right before this virus really changed everything. It was a beautiful experience, getting to meet the MAMOTH crew and the artists. Jenna Gribbon and I travelled there together. I feel like I only scratched the surface of London. I’d love to come back.

MAMOTH: What are you working on during the quarantine time? Do you have some plans?

A. Cudahy: The self-isolation and quarantine have been difficult. Everyone’s lives are just on hold or uncertain. This has wiped out so many people’s jobs and security. I’m hoping for the best, but it’s really a scary situation. My studio at Hunter is now off-limits. I have a small set up here at my apartment and can make works on paper and small canvases, in acrylic, which is what I’ll be working on for the immediate future, but losing the ability to paint with oils is a bit like losing a part of your body.

Anthony’s Studio @ Anthony Cudahy. Courtesy of MAMOTH

Anthony Cudahy (b. 1989, New York, USA) lives and works in Brooklyn and paints from found photographs, movie stills, billboard posters and queer archival iconography. Cudahy crops scenes, collaging and rearranging the characters to transpose the perspective. He has presented recent solo shows at 1969 Gallery, the Java Project, and Geary Contemporary in New York and was featured in a group show at CFHILL in Stockholm, Sweden.