On the occasion of Anna Solal's solo exhibition Le Bréviaire (2 June-22 July 2023) at MAMOTH, we are delighted to share an interview with the artist, going into detail about her use of materials, literary inspirations and artistic processes.

On the occasion of Anna Solal's solo exhibition Le Bréviaire (2 June-22 July 2023) at MAMOTH, we are delighted to share an interview with the artist, going into detail about her use of materials, literary inspirations and artistic processes.Translation by Naima Le Lausque.

MAMOTH: The title for your first solo exhibition in the UK, Le Bréviaire, refers to the liturgical book used in Christianity for praying. What led you to choose this title?

Anna Solal: I chose the title well in advance of the exhibition. A while back, I began drawing liturgical books in India ink, with a view to illustrating the cover of a book by J-K Huysmans, published by Jérôme Millon. I had experimented with this sculpturally as well. I liked the work at the time, but in the end, I didn't select it for the book cover, nor did I use it as a reference for the exhibition. But at the time, I was at the Villa Medici in Rome, visiting a lot of churches and listening to a lot of Current 93, and I decided to keep the title. In the end, the piece of sculpture I started to build representing the liturgical book became a smartphone, manifesting as a kind of appendicitis in the stomach of one the figures in the Three Girl Scouts piece.

Detail of The Sunflower, 2022, gas stove, plexiglass, drawing, paper, 110 x 190cm © The Artist, Image courtesy of MAMOTH.

M: You often describe your works as ‘painting-sculptures’. Could you expand on this term a little?

A: Inside works which blend sculpture and drawing, I incorporate further industrial and geometric elements – like in this particular series where I use pharmaceutical ampoules and gas stove tops. It is simply painting with a few elements in relief.

M: Though there is a great range in the materials and techniques you use, there is an overarching sense of balance and order in your work. Could you expand on your creative process a little?

A: A back-and-forth between what I want to do and what the form suggests is one of the main steps. There are many others that I can't necessarily describe.

M: How about when you start a project. Do you typically start with an idea and then search for materials to bring it to life, or does inspiration strike when you encounter objects that you want to transform into an artwork?

A: I don't really come across objects by chance, because I look for them and select them for their shape, texture, colour or meaning. The starting points can vary, I'd say it’s more about needing an idea.

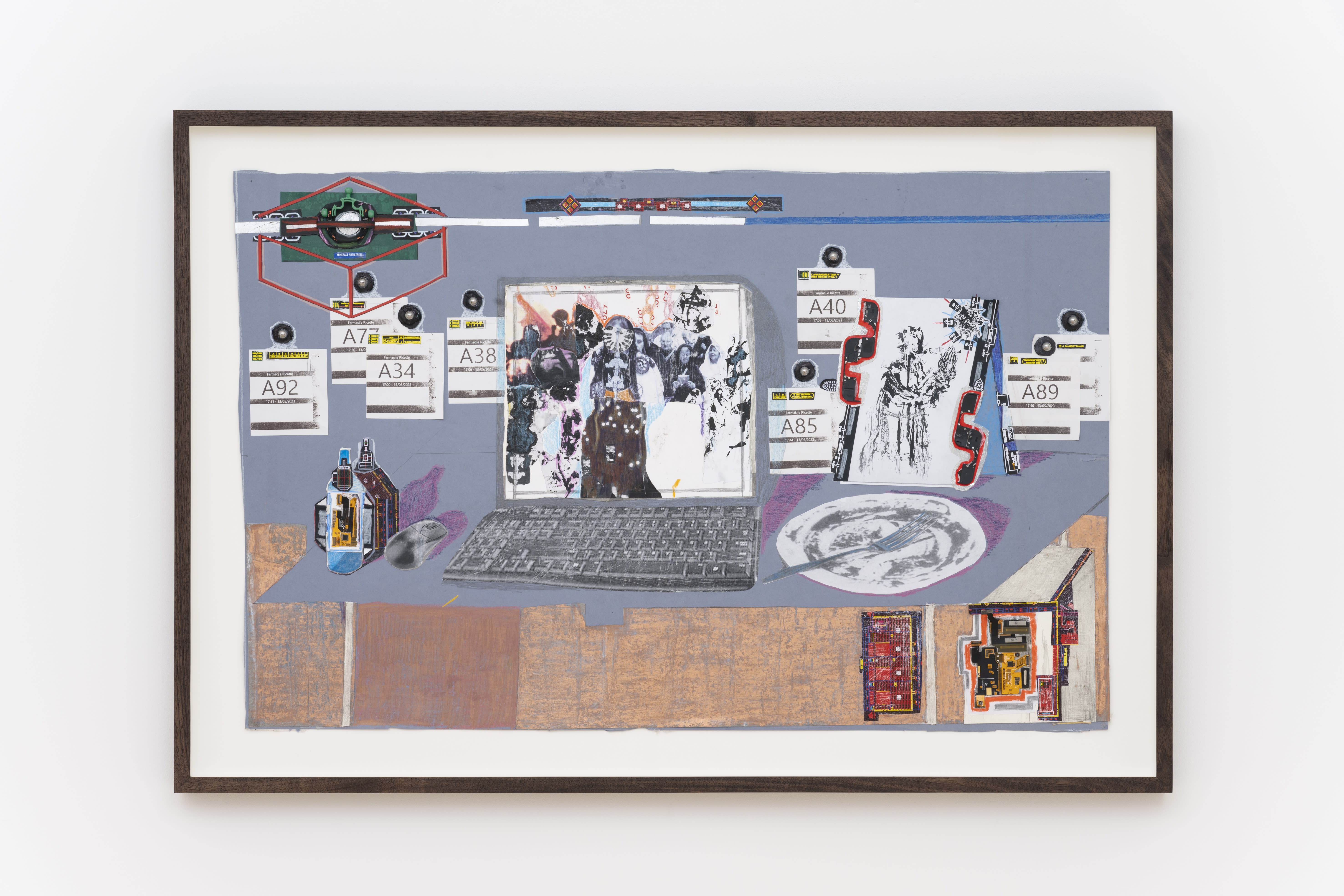

Detail of The Scout Girls, 2023, plastic, phonescreen, rope, paper and wooden frame, 126 x 91cm.

Portrait of Anna and a friend with Rosier et charnier de main, 2022, gas stove, plexiglass, drawing, paper, 120x90cm © The Artist, Image courtesy of MAMOTH.

M: It’s tempting when looking at the recurrent use of certain materials in your artworks, to ascribe significance to them. For example, is there any symbolic meaning to the use of rope in The Scout Girls?

A: Here the rope replaces the bodies. I often use rope because it allows me to draw in relief. No, I don't attribute a specific meaning to the material. I like that meaning can explode in many directions, the more the viewer appropriates it, the more accomplished the work is.

M: So in this case, functional objects are used purely for their formal properties. Would you say this sets up a tension between abstraction and figuration?

A: I'd say they're figurative, although within that figuration there can be more abstract areas too.

M: Speaking of figuration, let's look at some of the natural imagery in the exhibition. Can you speak about the significance of the donkey, and its relation to Robert Bresson’s 1966 film Au Hasard Balthazar?

A: The donkey, of course, is an animal with a strong spiritual significance. I didn't use Robert Bresson as a symbol of anything; it's just one of the many materials Alix Prada used to write her text, which she produced in parallel with my exhibition. I wanted to echo her text, transposing these donkeys into a landscape similar to that of a video game. Here, the donkeys are looking at each other and around them names of different nationalities float, slowly fading away.

M: Can you tell me more about the "video-game" aesthetic in The Donkeys? The pixelated message “what code is in the image?” seems to suggest a connection between technological functions and the human desire to read meaning into artworks. Could you expand a little on why you chose to include this in the work?

A: I use everything in my environment. The physical space in which we walk and the mental space that the digital sphere occupies have become amalgamated in our experience of our everyday life. Attentional capitalism is encroaching more and more on the way we explore the internet – we become trapped, sedentary in its web. Annie Le Brun talks about it very well by comparing the limitlessness of consumption to the infinity of desire.

M: Do you find that the theme of technology is becoming more significant to explore at a time when AI technology is learning to mimic human creativity?

A: Humor, guilt and self-sacrifice are all necessary components in the creation of a work. I don't believe for a second in the machine as a creative being. You can't invent the trembling of a work like Diane Arbus or Grünewald with A.I. On the other hand, what concerns me more is the way humans are being influenced by the language and mechanisms of this super-tool, even becoming enslaved by it.

M: By contrast, your work feels very connected to lived experience. For example, the rose bush and the charnel house in Rosier et charnier de main, seems to suggest a cycle of life – death, regeneration. Is that a theme you're interested in exploring?

A: Every work is a translation of something seen, read, heard, felt. There is metamorphosis at all stages of creation. Death too. By eliminating the possibilities of what might have been, what remains is reality.

M: A very philosophical observation! I know that philosophical writing often influences your work. Can you speak more about the literary references in Le Bréviaire?

A: I was lucky enough to be introduced to Edmond Jabès' Book of Questions by Alix Prada. In this book, various voices intermingle, and we don't know whether they're real or imaginary. The use of gas stoves in my work refers to this writer – a steel grid on which the writing of the drawing grows like vegetation, reclaiming its rights. Certain writers like Jean Genet have accompanied me for a long time, particularly in relation to my work around the suburbs. I refer to the writing of Ernst Jünger [The Glass Bees 1957] more frontally – for example, transforming pharmaceutical vials into the glass bees in The Sunflower.In the series of Procession drawings, Laura Vasquez appears wearing sportswear – an outfit which seems out of place in a landscape populated by mystic silhouettes, composed of flames and shoe soles. The work depicts a poet I met at Villa Medici.

M: As you return to certain references over time, do you feel there’s a sense of continuity between "Le Bréviaire" and your previous exhibitions? For example, the idea of the donkey in “Adresse aux Gémonies”, the natural imagery of "Le Jardin", or even the use of colour to evoke melancholy in "La Convalescence."

A: Obviously, there's a kind of continuity in what I do, whether in terms of subjects or technique. It's possible that in more recent works, animals are reappearing more frequently, or writing – whether through the presence of human names in The Donkey, or clothes exhibited at CAC Le Magasin in Grenoble, or even poetic fragments, as in the exhibition Flag created with Alix Prada.

M: Finally, where do you see your practice expanding to beyond “Le Bréviaire”? What do you want to explore next?

A: There are always projects in progress, maybe I would like to explore the theme of friendship and also danger. We'll see.

Le Bréviaire is on view at MAMOTH until 22 July 2023.