Seven large canvases line two walls of MAMOTH's basement in London, where Pu Yingwei undertook the gallery's inaugural international residency, the results of which compose the exhibition A Study in scarlet: The re-origin of revolutionary realism (2 October-13 November 2021).

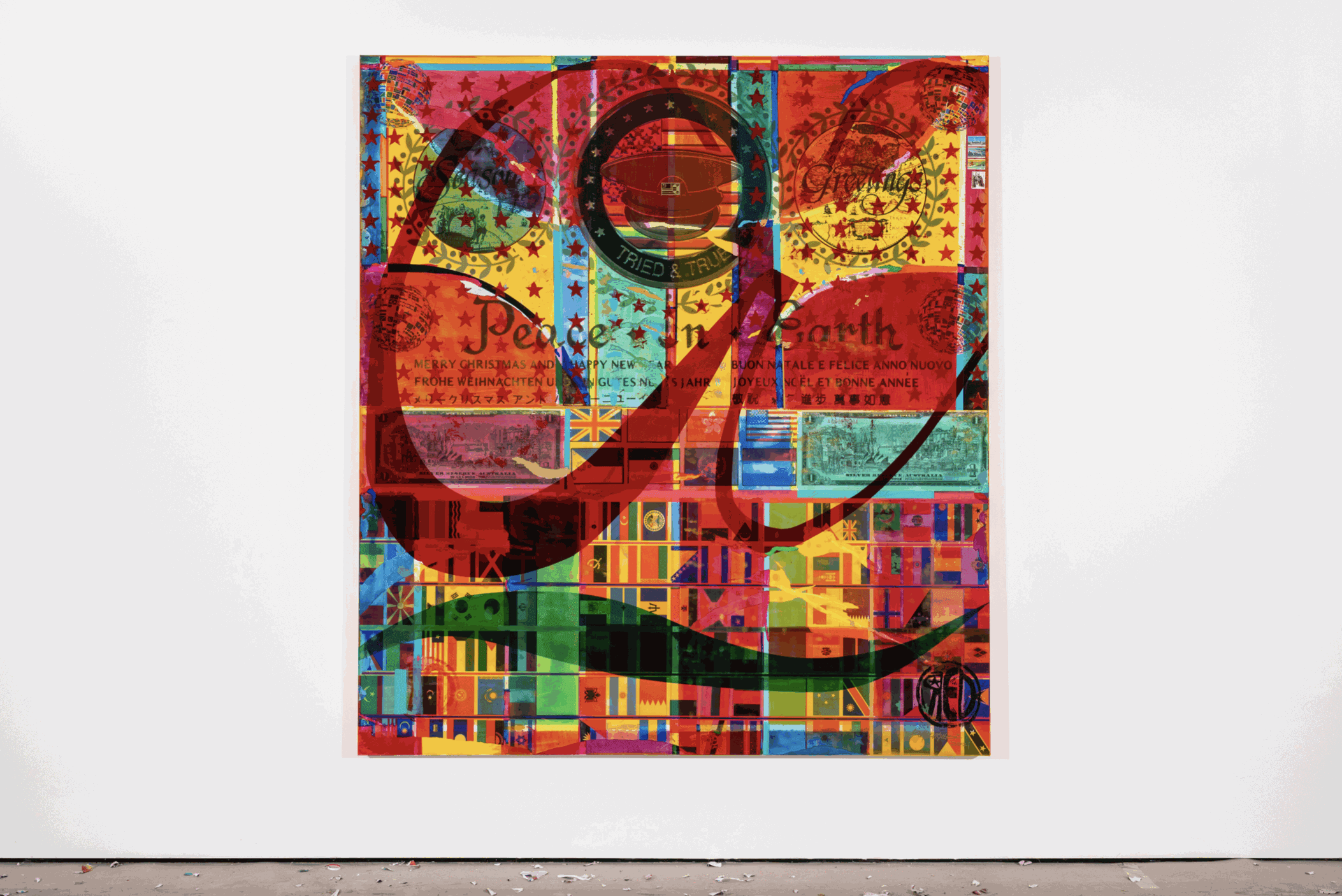

These mixed-media paintings, composing 'A Study in Scarlet' series (all 2021), are united by a dominance of red, with washes of colour intercepted by constructivist lines, curves, and stencilled shapes under which prints and stamps have been pasted.

Each composition constitutes a complex text: an interrogation into globalisation from a maximalist perspective.

In New Geography (Two Types of Red Colonies), a grid of silver stars primes a canvas divided into four sections, marked by their opposing blues and reds. Overlapping covers of the state-sponsored ChinAfrica magazine, founded in 1988, appear on the bottom right corner over an image of the globe washed over in blue: a nod not only to the Belt and Road Initiative, but to China's historic relationship with the continent that followed the 1955 Afro-Asian Conference in Bandung, after which Mao Zedong re-conceptualised the 'Three World's theory.

Throughout the painting, there are gestures towards the Cold War, whose U.S.-U.S.S.R. power struggle the Bandung Conference and following that the Non-Aligned Movement sought a way through, and the space race that in part defined it.

Above the ChinAfrica magazines, a space satellite emerges through the red, with the golden stars of the Chinese flag. Five 2019-issued stamps affixed to this scene celebrate scientific and technological innovation in China, including a picture of the Chang'e-4 lunar probe.

Neighbouring this frame in a nod to Sino-Soviet relations, the image of an astronaut with U.S.S.R. printed on their helmet in Cyrillic seeps through a blue wash. From here, silver lines curve down to where 'China Capital' is stencilled in gold in Coca-Cola's cursive script: an expression of China's evolution from Communist outlier to global, capitalist superpower.

Steeped in globalisation's macro histories, world flags take up the bottom half of Sovereign Police (Celebration), capped by two 'Lunar Dollars' featuring iconic world architectures, from the Taj Mahal to Burj Al Arab, above which 'Peace on Earth' is printed through the middle.

Topping this painting off is an emblem showing a police cap with a flag design for global China, the motto 'Tried & True' printed below it.

At face value, this all looks like a triumphant celebration of globalisation with Chinese characteristics. But other paintings complicate the frame, probing what globalisation means based on what is has been.

---

This is where London comes in—the dark heart of a former imperial power whose spoils are reflected in a taxonomic grid running through Anglomania (Museum): red line drawings of skulls, masks, pots, and figurines inspired by the British Museum, which lead into faces of peoples from across the world drawn in black lines. Cutting across the whole surface are bold strips marking a Union Jack turned on its side.

---

Hovering over this scene, a clawed hand reaches for a globe: an image recalling the invisible hand defined by Adam Smith to describe capitalism's self-perpetuating logic, as much as the face of Dracula etched into the next canvas.

The Gentleman of Communist Capitalism is an anomaly in the series, with barely a print priming the underside: a chequered monochrome of bleeding red text written in the artist's ideogramic font merging English and Cyrillic. The script talks about a post-pandemic world after Western collapse, when 'red internationalism became the best choice.

Dracula is a metaphor, the artist tells me: a monster that Bram Stoker created in the 19th century to embody the industrial and economic development accelerated by British imperialism, whose domain comes through in the canvas that follows.

Bordered by 'China Capital' on one side, a lush flurry of green strokes surrounds faces and flowers that align with three stamps pasted above them, one from 1982 depicting three overlapping profiles in graphic blocks of colour—white, yellow, black—and one from 1973 bringing those graphics to socialist realist life.

But while these stamps—and in turn, this painting—seem to visualise the bygone dream of an international communism as a prelapsarian paradise, its title, When the World Becomes a Plantation, refers to something more sinister when considering pages from colonialist, 19th-century anthropology books barely visible below the pigment.

---

In these oppositional and overlapping histories, viewers are challenged to not only think about the histories that have defined the course of globalisation, but to consider the legacies and ideals that have been sidelined in the process.

Take the 72 flags ranging from Angola to the U.A.E. forming a column in Modelling History (Revolutionary Art Skills). Among them is the flag of Dravidar Kazhagam, a movement that emerged in India in the 1940s seeking to abolish the caste system—a symbol hiding in plain sight posing difficult questions about culture, politics, and social contracts in a changing world.

---

There is no easy way to read all of this. As the artist says, these paintings embody a paradox. Each one says different things depending on who is looking. Take the emphasis on internationalism and its histories, which confronts the hyper-nationalist perspective that tends to infuse the superpower mentality; or the folding of imperialist histories into new trajectories.

With that, Dominators of the Red Planet, the final canvas—or first, if you read the line from right to left—offers a point of departure, in which the giant Dracula filling one canvas is replaced with a giant reverse red R that looms over a grid of faces showing men the artist calls 'future dictators'.

It's an interesting equation. Where R—whether for red or revolution—inhabits the place of a monster that communism has historically sought to overthrow, as future monsters linger nearby.