On the occasion of Sangram Majumdar's and Li Heidi's inclusion in the group exhibition The Glass Bead Game at MAMOTH, we spoke with the artists about their work.

MAMOTH: We should say from the beginning that there’s a nice connection between you both separate to the group show, at MAMOTH, as Sangram you taught Li Heidi in Baltimore. Let’s begin with you both explaining a little about how you came to art, was there a trigger or someone who influenced you to begin drawing and painting?

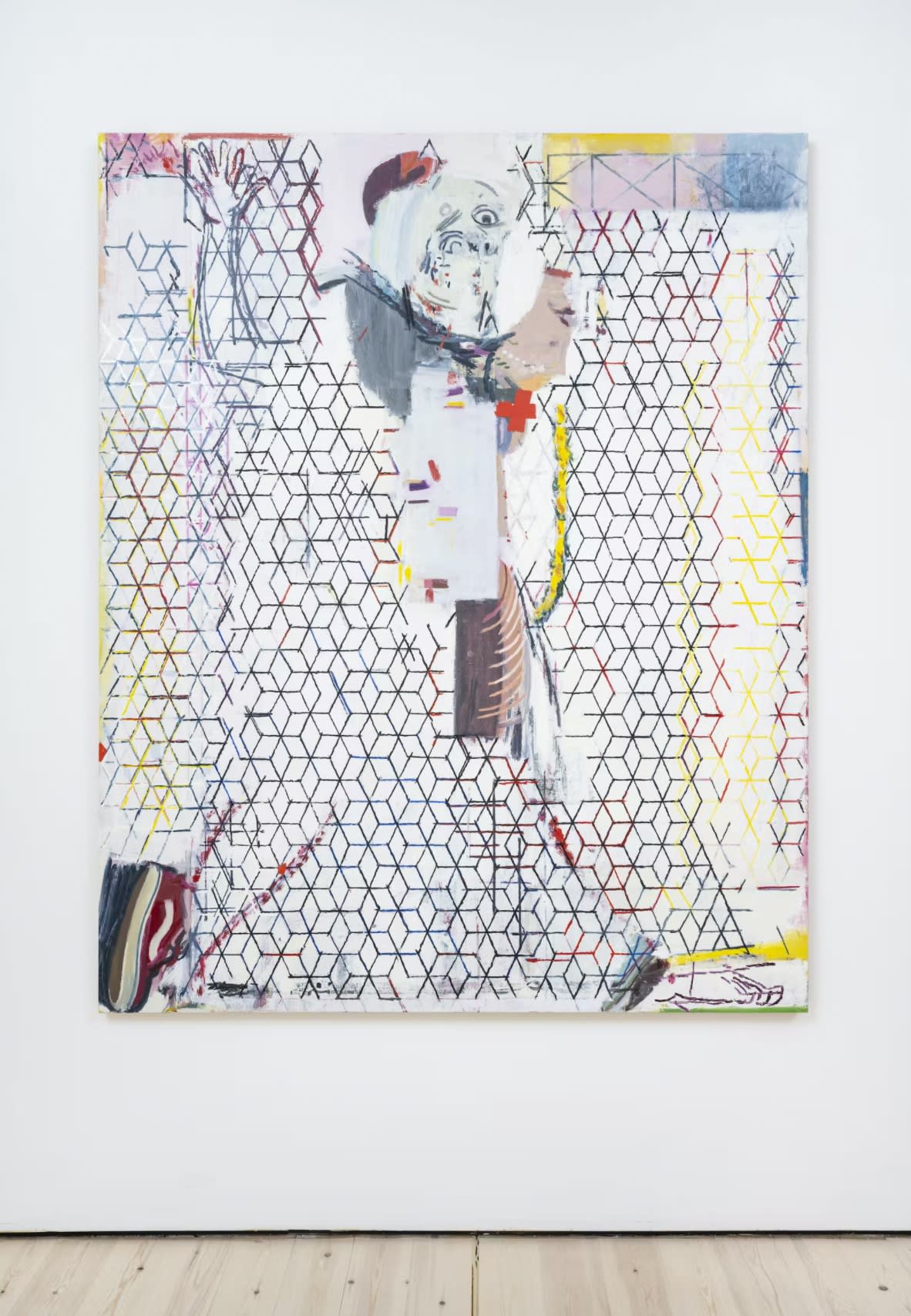

Sangram Majumdar as part of the group exhibition 'The Glass Bead Game', installation view, MAMOTH.

Sangram: I am not sure how I came to art. I do know that I have always been drawing, since I can remember. As a kid I used to accompany my dad and my uncles to various Hindu festivals in Calcutta and draw amidst the crowds. I also remember cutting out images of cricket players from Sunday newspapers and making my own compositions. My dad also loves to draw, and I suppose he was my first drawing teacher in a way. Somewhere in there it stuck, and I just kept doing it.

Heidi: Drawing to me is a primitive need. Perhaps, it was because I was obsessed with watching TV when I was a toddler. And when I wasn’t allowed to watch TV, I wanted to create my own TV by making characters/plots/worlds through drawing. These worlds that I created are the places I could escape to when I felt so out of the place in the real world.

M: We’re speaking on the occasion of your inclusion in The Glass Bead Game at MAMOTH. Perhaps we could begin by picking up on a line from the press release, which I think nicely bridges both of your practices. 'Each artist engages with visual fragmentation and repetition…referring to the artist’s own life, or commenting on how life can be experienced as something impressionistic and nonlinear.’ Perhaps Sangram, you could begin by discussing this quote in relation to your practice, and how it can be applied to its concerns both technically and theoretically.

S: There’s a lot I could probably say about this, but I will start by saying that I agree with this quote completely. Technically speaking, my work is very much a result of time. I work in multiple sessions, and over time areas get painted over, or removed, while new decisions come in. Sometimes the paintings change drastically, but somehow that’s what it takes for them to come about. I think a lot about how the past and the present live next to each other all the time in the world, whether it’s an old building next to a new development, or my daughter spending time with her grand-parents. I want this in my painting. Theoretically speaking, I am interested in the language around opacity and the body that Dr. Fred Moten explores in his writings as well as Sara Ahmed’s and Maurice Merleau-Ponty’s writing on phenomenology.

H: I paint in the way that I experience life. Life is inconsistent, fragmented; dreams and memories are often meshed together, it is hard to tell what has actually happened, what was experienced in a dream, and what was a made-up story. I have learnt to accept the blurred dimensions of realities, the possibility of everything. I realised the tangible imagery could no longer capture the glimpses of my truth. I want to tell the whole story, the sum of all possibilities, which is too big and too complicated to be told in a linear way. To fragmentise, to paint over, to erase, my process in painting is a metaphor of the constant battle for acceptance. Not only to accept the rigid social/cultural/sexual identities, but more to accept those inconvenient but very humanly sentiments as if to accept the way each stroke falls onto the canvas. Every mark is true to its moment, though some are painted over, some are erased, some are broken, and some are left out, they still exist simultaneously in different layers of reality.

M: You both use the body in a very distinct way, whether in silhouette, in the background, or occluded in some way, could you talk a little about this?. Do you consider yourselves portrait painters?

S: That’s funny. In some ways I think every painting that I make is a portrait of some kind. But, I don’t usually set out to make a portrait in the traditional sense, or haven’t for a while. Maybe I should do one.

H: I might be a portrait painter of fictionized worlds and unrealistic things. The forms and objects in my works are possessed by body like qualities: the ghostly water splits into mirrored/anti-mirrored realities, the ferociously growing stems/veins/shadows submerges into the foreground, the translucent membrane withholding the motherly liquid from afar.

M: You both use your own photographs, film still frames, and personal observation in your paintings. Could you describe a little about your use of source material and inspiration for your paintings?

S: Sure. As my practice has progressed I have become more interested in exploring how to use liminality as a condition around which to create. For example, the walking figure that appears in Becoming 1 is built from a range of parts including my head, my daughter’s shoe, a torso from a miniature painting, and other bits. The grid itself is pulled from the pattern that exists in crossing street signs in my old neighbourhood in Brooklyn. Meanwhile, Spring is made from drawings from movies on my phone.

H: I love collecting screenshots from films or TV, frames with striking composition and colours. I print the screenshot out but rarely use them directly as reference, instead, I try to memorise them and digest them, then the colour and the forms and mood from the films organically unveil from the white canvas.

M: You both left the country of your birth, and in different ways refer to the liminal space that is to live in one distinct context whilst bringing in your own cultural identity, can you explain a little about your approach to doing so, and how this comes out in your painting?

S: For me this has been and continues to be a work in progress. The tension that this creates has become more and more a place of real invention and exploration for my paintings. I am always pouring through my images to see what to bring into my work. The main thing I try to keep alive is that sense of fragmentation and dislocation in my paintings. My goal is to always use it as a space for new creative decisions.

H: I tend to use contrasting textures and thickness within one image, creating two polarizing yet interconnected mirroring forces, suggesting the complexity and multi-layered nature of two beings as one, like the home is to the faraway lands.

M: How does living in Seattle (Sangram) and London (Heidi) influence your practice?

S: I can say that since I moved to Seattle, I have been thinking a lot about weather and environment and how it affects how we experience and navigate our spaces in real time. It’s really interesting that here the weather can sometimes shift from fog to rain to sun all within an hour.

H: As a student in Baltimore, I was more influenced by the college experience of going to art school (MICA) than living as an adult in Baltimore. Taking Sangram’s class was one of my most memorable times in Baltimore. I really looked up to Sangram and I wanted to impress him, so I spent a lot of time painting. But Sangram saw that I was trying to 'paint to impress', and he gave me the most honest criticism; that I don’t need to try so hard to fit the frame of a 'good painting' like a goody-goody child tries to get straight 'A's. He told me it’s okay to go wild. That really struck me, I think I almost cried, I thought of all the years growing up that I had been such a try-hard, living my life timidly to fit the image of the 'good’ daughter, the 'good' student, the 'good' partner... I felt that he had seen through me and understood my struggles, and that moment was monumental, where I began to battle the need of “paint to impress” and really let myself go in painting and in my personal life.

M: Equally both of your practices could be described as a process of synthesis, bringing together observed images, cultural identity, everyday life, a sort of hybrid of elements, painterly representation and abstraction. And in a way the everyday and the fantastical. How would you feel about this view of your work?

Li Heidi (left) as part of the group exhibition 'The Glass Bead Game', installation view, MAMOTH.

S: I agree. Although, I am always hesitant to attach my name to those two painting modalities. I think to call them paintings is enough.

H: Everyday living is fantastical. I agree with this view, and moreover it is the undercurrent of love and pain hidden within these hybrids of elements. I’m obsessed with Haruki Murakami’s writings, where the mundane reality is a bit off. There is one part in Murakami’s book The Wind-Up Bird, where a character says that sometimes you put instant pudding into the microwave but when it finishes and you open it, you find macaroni. There are two kinds of people in the world, those who believe that they must have put macaroni in and just remembered it wrong; and those who insist that they put in instant pudding, but somehow, the reality had shifted, where the pudding was no longer pudding in this world, and had been replaced by macaroni. I should be shocked , but I’m quite relieved that sometimes I get macaroni when I put in pudding; this feels a lot more real.

M: You both deploy intuition in your work, where the image reveals itself through its own making, could you elaborate a bit on this perhaps?

S: Well, one way intuition kicks in for me is when I am trying to figure out what the next painting would be or how to move forward from feeling stuck. I draw a lot and also print out images of my work and alter them constantly. I do believe that moving things around with my hand often will unlock an idea that I could not have arrived at in any other way. For me, I am suspicious of overthinking or over-planning. So, even though I draw and redraw and make a ton of mixed media variations, the painting always has its own reality.

H: I like to start a painting by creating chaos, intuitive scribbling onto the canvas, a flood of raw impulse. Then I assess the chaos, the process is like ancient people reading burnt turtles shells as divination in Shang dynasty(甲骨卜辞). I slowly find order in this chaos and enforce the order, the canvas becomes the battlefield of different forces, by sacrificing some marks that do not contribute to the order, a new layer begins to form like the rising of a new era in the history of this piece of canvas. Every painting day is a struggle, constantly balancing the weight of order and chaos, colour and form, abstraction and figuration, birth and sacrifice…what I’m looking for is a comfortable state of the collision and complementation of the forces, a dynamic balance of the light and the shadow (阴阳和合)

M: John Yau wrote in Hyperallergic of your work Sangram, that ‘It seems to me that Majumdar is after that moment of seeing which occurs just before we name the object’ - it feels like this is both something you have in common in your work. In just the same way that Heidi’s organic forms whilst in part tangible, aren’t fully legible, they evoke the sense that they are in the process of becoming, how would you both respond to this observation?

S: Well, John wrote that in relation to paintings I was making from direct observation I believe. But I do think that I am very much interested in redirecting or reorienting the viewer away from any direct readings. This is where my interest in opacity, distortion, layering, and fragmentation come in.

H: I think a lot of my paintings are about being caught in the act, and some of them are about to burst into a pile of water, some of them have already drowned in the water from their own burst, and some of them have already died from drowning and entered a world of ghosts. All these images have strong suggestions of temporality, like momentary peace in the constant years of war.

M: What paintings and artists did you both look at when you first started making work, and perhaps are there artists now you still look to for inspiration?

S: For sure I go through stages of looking and learning about artists. When I was a student I very much poured over artworks. I remember seeing an exhibition of John Singer Sargent’s paintings at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston and feeling blown away. Although that feeling didn’t last too long, especially after I visited Madrid and saw the Velasquez paintings. When my paintings were rooted in direct observation, I was very interested in the works of Euan Uglow and Frank Auerbach. Now I am more interested in reading about artists and reading what they wrote. I try to read a bit from the Jack Whitten diaries every time I am in the studio.

H: Liu Xiaodong, Cecily Brown and Doris Salcedo inspired me a lot when I first started making work. Now I look at a lot of films and literature, I really love films by Lou Ye and Fruit Chan.

M: How long do you focus on one painting, do you ever put a work to one side and revisit it? And do you focus on one painting at a time, or multiple?

S: All of the above. I don’t have a set system. Sometimes I get really frustrated and put a painting aside. Other times I just paint over it, and regret that decision a month later. But that’s life!

H: Multiple. Sometimes I would leave a painting for months knowing it’s lacking and one day I turn it around and resolve it by what I knew months before but didn’t feel right to execute then. Sometimes, unresolved paintings are like new love affairs, you just don’t want to move on from the ambiguous state of infatuation.

Sangram Majumdar in his studio, photo by Caleb Kortokrax.

Sangram Majumdar (b. Kolkata, India) is an artist living and working in Seattle, Washington. Majumdar paints with oil on canvas and linen. Majumdar’s work is immediately recognisable for its unique synthesis of abstraction and figurative style, often rendered in a combination of painting techniques. Layering myriad cultural references, Majumdar straddles a territory of the everyday and the fantastical. When present, the repeated motif of the shadowy striding figure is a key protagonist. Furnished with decorative, multicultural patterns, he successfully incorporates a vast range of sources and styles, to create an entirely unique language of his own.

Li Heidi (b. China) is an artist living and working in London.Heidi’s painting practice deals with the complexities of image making. Without pre-planning, her canvases tell the story of their own making. Her work is a composite of many references, including the colour palette and freeze frames of Chinese cinema, everyday objects, and nods to her life split between her childhood in China and her recent life in Europe. Keen to embody the sensation of desire, Heidi relishes joyous combinations of forms and colour, completed with a vast variety of brushstrokes. Her compositions allow human organ-like forms to play out a game of hide and seek.