MAMOTH: Your solo exhibition The Watery Realm, at MAMOTH is your first in the UK, and will serve as an introduction to your practice for a number of people. To begin at the beginning, when did you first start to draw or paint? and what prompted it?

Julia Adelgren: As I grew up, it was something that came and went, that I did in periods. When I was twenty I started to dedicate myself to it completely. I think I had something inside me that restlessly needed to find an expression. I also worked with other materials parallelly in the very beginning, like textiles and strange flea market finds, but soon it became clear to me that everything I was searching for, I could get closer to with painting.

M: The title, The Watery Realm is taken from Yuko Tsushima's story of the same name. The story is an exploration of maternity, time, memory and loss - could you perhaps explain your inspiration behind using this title?

J: It's true that the title of the show comes from this story. It has a glimmering language with descriptions that awaken something in me. I like how Tsushima moves freely between the unspeakable, the underwater world, and everyday scenes. The Watery Realm is also the title of one of the works in the exhibition. I was reading the story for the first time when I was working on this painting, and it seemed to have a lot to do with what was happening on the canvas, and, as I thought later, had a connection to the rest of the work in the show too.

M: The exhibition presents a selection of works produced over the last four years. Is there an overriding theme or area of focus that ties this body of work together?, and can you see how your work has developed in this time?

J: All works except Thee Who Seek, Thee Who Shouts, Thee Who Seeks, are no more than a couple of years old. I feel that it fits in with the newer paintings in a way that many of the things that I did around that time don't. I think that several paintings from 2019 onwards have a certain focus, making them more intense somehow. Something happened then, I can't really say what, but I think that I began to see things differently.

M: The scenes you depict have a timeless quality, as if existing outside of general time, whilst also possessing a very contemporary interest in psychological compositions, is this duality something you think about when making the work?

J: It's not something that I think about in a conscious way while working, but I think that those things are important to me. I instinctively make changes if things get too obviously bound to a certain time. I never thought of the psychological as being specifically contemporary, but maybe it is. If you look at the most interesting painters, Velasquez, Hammersøi, or most definitely Munch, you also often find psychological compositions, but in a time where painting as a medium of documentation has been taken over by photography, I suppose that the psychological aspect becomes even more important. One of my favorites in creating psychological tension is Rainer Werner Fassbinder. Particularly in many of his 70's films, like Martha, Fear of Fear or his versions of Ibsen's A Doll's House or Fontane's Effi Briest. It lies in the dialogue and the acting of course, but above all, in how he constructs his frames to tell the story.

M: Tsushima in The Watery Realm uses the metaphor of the Shinto water god, Suijin, and looking at your work, water, ranging from flowing waterfalls to larger bodies of water appear frequently, could you perhaps expand on the reason for this?

J: I never really decided to paint water though it frequently appears in my work. However, I am always observant of water, of the reflections and what is happening there. Whether it's in a puddle on the street, in a pond or in the sea. Especially living in a city, water is a big source of excitement. It's always different, ever-changing, even in an environment that does not seem to bear much natural life. Also when the sky is plain steel gray, the water is always playing tricks with its surface patterns and ways of catching light, always hard to define.

M: The way you create each painting is very unique to each canvas. We have discussed before how even just a colour or a texture can spark a whole composition. Can you discuss the various starting points?

J: That's right, there are paintings that start like that, just with a colour or a texture. Sometimes the whole picture comes quite directly, almost completely without reference pictures, though it always takes time to make it work to the detail. Others are long complicated journeys where everything changes beyond recognition many times before they are finished. For a long time they can be like sand paintings, coming and going, shape-shifting. I think that many things are discovered on these journeys, and that by being in this painterly world so much, new pictorial ideas are born, for other paintings as well.

M: Constructing and preparing a canvas with your own hands is very important to you, why is this?, and how does it inform the paintings you create?

J: Yes, most people did it like this in Düsseldorf, but before I went there I hardly knew anything about it, so for me that was really great to learn. In general I feel like there is a stronger connection to the material with a self-prepared canvas. The colour goes much more into the linen, the way I prepare it, not too thick with the base, and I get less trouble with very shiny surfaces and things like that which often occur when you paint a lot of dark colors. You can control how 'thirsty' you want each canvas to be, which opens up possibilities.

M: As a follow up question - the pronounced textural quality of your paintings is so apparent when seen up close, in person, could you talk about how you build up surfaces in this exhibition, and what techniques you use?

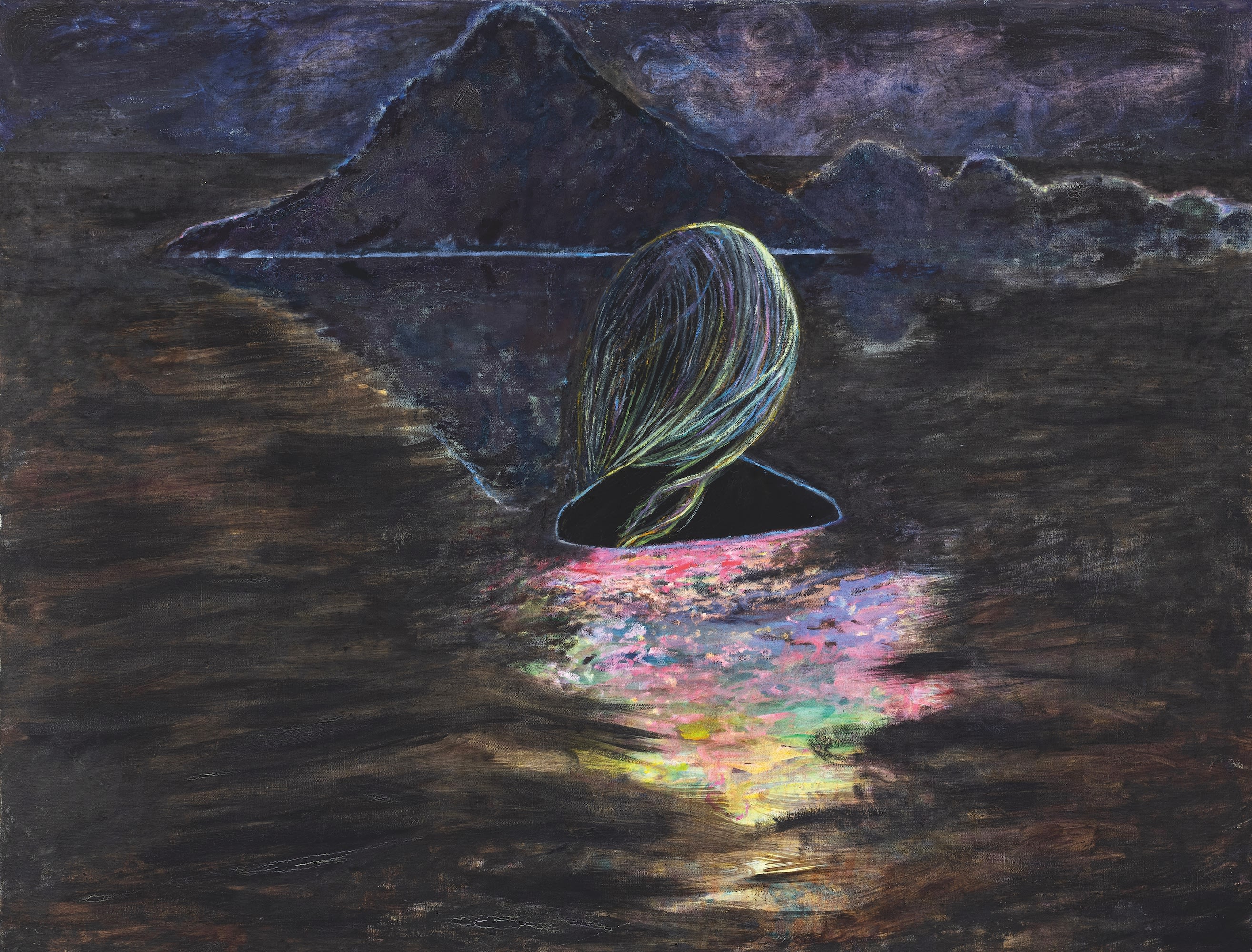

J: That is also very different for each work. It's not often exactly planned right from the start, but rather a dialogue. For example, I had made a large, quite rough canvas that I had in my studio, that then was very suitable for an idea I had when I made the painting The Watery Realm, and that was to work with a sticky, honey-like oil mixed with paint and letting loose pigment stick on to it. The roughness of the canvas made it possible to hold all that colour and pigment in a specific way. If the canvas had been finer, then the painting would most probably have gone in a different direction. For Iridescent White on the other hand, I found it suitable to paint it on wood. The material is attractive in itself, and I wanted to keep the painting rather thin and light. For me, that wouldn't have worked on a rough canvas.

M: Your work appears to communicate with historical landscape painting, evoking historical romanticism, at the same time addressing contemporary questions of psychology, storytelling and mark making, can you speak more about this?

J: To express myself through landscape always came very naturally to me. I observe it when moving around in the three-dimensional world, and I love to look at how it has been depicted through art history by artists like Corot, Monet and Bruegel the elder. Japanese wood print tradition is also always present for me. I often get the feeling that everything here is solved in a landscape way, also when the motive is for example a room with a figure. That said, I get a lot of inspiration from completely different directions too. From literature and music and from what I sense is happening around me and within. I also see a lot of films. It's just such a treasury of images in a context, loaded with meaning. If I see an interesting frame I will pause and make a screenshot. Sometimes I then print these images to use them in different ways for painting.

M: Are there any contemporary painters who inspire you, or whom you simply admire, Nordic or otherwise?

J: There are some that I really like, and I think that I am probably very shaped by painting today, because it is around us all the time. Therefore I can also feel a need to keep a certain distance to it. I love going to a show and seeing good contemporary painting, but I don't study it too closely in detail, later in books, like I do with historical painters. I sometimes feel like it takes me longer to connect with my own voice if I do that too much. We already have so much in common by living in the same age, and to as large extent as possible I want to create from my feeling of existing, rather than unconsciously aiming to create something that looks like contemporary painting.

M: Is there a method to how you organise your source material? Do you constantly archive and store your references with a view to be used at a later date?

J: I suppose that a lot of things are stored in mind for later use, but I usually use what I have collected physically quite soon. If I for example freeze the frame at a specific time in a film, then the urge to do that usually comes from something that occupies me here and now, and that needs to come into the painting at that moment. Frequently there is a connection between for example seeing a specific flower in bloom and wanting to paint it, so the observation from life and the act of painting is often closely linked for me. However, I also keep many books with pictures around me, and those I store and go back to in a different way then I do with the single images.

M: Mountainscapes and forests are recurring elements in your work, do these point to particular sites or are they imagined?

J: They are sometimes loosely based on other pictures, and sometimes completely imaginative, though I think they also derive from my time in Bergen and growing up next to a forest. If I start by looking at a photograph, the end result is always very different, because before reaching that finished point I have felt that something is wrong. I think that my painting is a lot about blowing life into the pictures. Making them become what they are, not what they could be. The title often becomes clear to me somewhere in the middle of the process, and then it's about making the title and the character of the painting one. At this point everything can still change - the motive, the colours, even the size of the canvas. But the title usually stays the same. Though being highly influenced by places I have seen, the paintings always represent a scenery that is their own, that exists only there, or somewhere in my mind.

M: Is it correct to observe the influence of nostalgia in your work?

J: There is definitely a strong influence from other times and places in history, but I don't really think that I am very nostalgic, no. Some things may have been better in other times, but other things have been worse. There is a longing for something else, but I'm not sure what.

M: How much does the context of your place of work inspire your painting?

J: I think that the context of my place of work is essential to my paintings. Both in terms of what there is to look at there - in the landscape or cityscape, and in terms of my own situation and that of the people around me. As well as the character of the place itself, its history and what can be sensed there. I also think that the compositions of the paintings are dependent on my position in a room, and that the gestures of the brush strokes are affected by for example how high the studio-ceiling is. How you are able to move about in your mind and in your room is crucial to what the work turns out to be I think.

M: On the subject of your studio, could you describe your studio setup?

J: In my studio I work moving around a lot, I hardly ever sit down. I need a lot of space behind me in order to do something on the canvas, make a mark, and then go back to see what it does to the picture as a whole. So I move like that constantly, back and forth in the room. Frequently I listen to music, and I often work afternoon to evening or night. I try to do other things that have to be done before, because I don't like to have a specific time that I have to leave or do something else.

M: You studied in Sweden, then studied under Tomma Abts at the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf, how was this experience for you, especially working in Dusseldorf which has such a strong history connected to painting, did this bring about any particular developments and changes to your practice?

J: I studied some preparing art school years in Sweden, but did my whole art academy education abroad, first in Bergen (Norway) and then in Düsseldorf (Germany). Coming to Bergen was fantastic. The town is surrounded by high mountains on which white clouds move slowly on the many rainy days. I found it fascinating, how there could be earth so high up in the sky. In Bergen it is also very easy and available to walk up the mountains, where there are old woods and huge green dripping mosses, and higher up, more naked grounds. I spent a lot of time outside there, drawing and making watercolors, taking photographs - trying to capture something of it. Coming to Düsseldorf was also very exciting. It is such a big academy with a huge variety of positions, and a great number of painters. There is a lot of knowledge and a society around painting and material that is quite extraordinary there. The Düsseldorf Academy has a very special energy, it's like a world in itself. It can give you a lot, but I think it can also swallow you up.

M: The exhibition at MAMOTH has a notably nocturnal character, when figures are depicted, often they are alone, they're faces obscured, or body partially out of the frame. Could you talk a little about how you design your compositions, do you work from preparatory sketches?

J: I don't work from sketches in a direct way, but feel my way to the picture. I like sketching though, looking at something and depicting it directly on paper, or waking up and describing a dreamt image with words or drawings. This is something I do in periods, and I feel that it has a big influence on the studio practice, even though I rarely actively use them as source material. Sometimes I am surprised to find notes about pictorial ideas that I forgot about, but nevertheless have gone through with.

M: Light and shadow are key focuses in the exhibition. Could you talk a little about what comes out of depicting darkness?

J: Darkness has always been there in my paintings, and I have had to find ways of refining my depiction of it. When you contemplate it, it becomes increasingly clear how wide a subject darkness really is. It can be all kinds of shades, colors and textures, and through that communicate very different things. Sometimes the paintings have had a tendency to get lost in darkness, and I have had to let in so much light that it is possible to tell the story.

M: There is a very strong literary presence to your work, how much consciously do you allow literature to influence your painting?, and if so, are there particular writers who you admire?

J: It's true that literature has a big influence on my work. I think that reading is a bit like dreaming together with someone. The words are given to you, and pictures appear in your head, that are built of memories and imagination. I never read something and then decide to make a painting from that, the content has to be found in the process. The stories or images that reach me through reading integrate in the paintings very naturally, because I use them to discuss things that are on my mind with myself. I suppose it's all about what you are susceptible to in your life at a certain time and place. One writer who has meant very much to me is Patrick Modiano. I like how the narrative is often tuned down, leaving more focus on the atmosphere, and the mere presence of the people. Often I feel that his books are vibrating with darkness. Though he never goes much into details, he has a way of making you strongly sense it. Then these fantastic sequences come in, where you seem to sort of leave time and space and look at things from some far place. I feel like his way of writing gives you an opportunity to just be in his world and find the poetry within it, without forcing anything upon you.

M: Japanese culture also appears to be an influence, could you expand on this?

J: Yes, I find many parts of Japanese culture intriguing. I already mentioned the wood prints, and another example is the tradition of ghostly stories such as those depicted in the wonderful films Kwaidan (1964) and Mizoguchi's Ugetsu (1953). There are also newer parts of Japanese culture that I really like. Anime series such as Rose of Versailles, Galaxy Express 999 and Sailor Moon I find very interesting. Both in terms of story and content, and visually, in how the pictures are composed.

M: "I think that my painting is a lot about blowing life into the pictures. Making them become what they are, not what they could be". To quote you from a previous answer - could you talk a little about your relationship to images, and the idea that you are somehow encouraging forms into existence?

J: The starting point is always sort of a suggestion. Although I may have an idea of wanting to make, let's say, a thinly painted work in an orange color scale, that doesn't mean that this is where I really am or should be going. If I have a strong feeling for it, I will act it out on the canvas, but it is far from sure that it will stay. Some trace of it might do so, as a texture in the background or as an orange line of light around a figure's head, but the idea of doing something and actually pursuing it are two different things. I'm not so sure that we know that much about who we are and what we want on a level where we are reasoning, that is something that lies deeper, and that is harder to grasp.

M: It feels like there's a push and pull between the past, present, and future in the paintings, would you agree with this?

J: I like that interpretation, so I hope so. I sometimes think that they are a sort of meditation on being, a feeling in the body and mind of the here and now. Perhaps that leaves you in a past-present-future space, since "here and now", and what that means, of course is a very fertile subject.

Julia Adelgren, Iridescent Blue, 2021, oil on canvas, 105 x 170 cm © Julia Adelgren. Courtesy of MAMOTH.

M: Iridescent Blue stands out as it possesses a very different feeling to the other paintings, the skewed perspective gives it a very playful character. A departure from other work, do you see this as signalling a possible future focus or direction?

J: There was a period during this year and the last when many paintings just didn't want to have any ground, but to merely be a reflection in water with something resting on it or flying close above it. I made some paintings of this character. The painting Ether is one of them too, though it might not be obvious to understand it in that way. It seems like I'm through with it for this time though, because I don't see the paintings I'm working on at the moment ending up there.

M: Finally, what are you currently working on in the studio? Does it follow on from The Watery Realm?

J: I have three paintings going at the moment, and it seems like they are all on land without any water in sight, but we will see.

Julia Adelgren's solo exhibition is on view until July 3rd at MAMOTH. To view the exhibition, please click ➞ The Watery Realm

Julia Adelgren (b.1990 Stockholm, Sweden) is an artist living and working in Copenhagen.