Nature, creatures, and myths under the brush of Alessandro Fogo tell great secrets: to know the sun, to hold the hand of all things, to see. The sky changes from clear to deep blue and all the full peace of an unmanned land descends, sinking into our imagination. The title of this article is inspired by the anthology of Polish poet Wislawa Szymborska, “All is Silent as a Mystery": nothing is ordinary or normal—no light of day, no evening following on its heels, and, especially, no existence of any kind, no existence of anything upon this world.

Each of Fogo’s subjects is filled with profound archetypal symbolism. For Italian painters, this is a cultural touchpoint. The ideas and objects he depicts have survived the passage of time; they are the spiritual rituals and beliefs of mankind. Fogo is fascinated by the semantics of objects and his paintings are imbued with mysticism, like a David Lynch movie that draws the viewer into a labyrinth of narratives where nothing is what it seems and something could mean anything.

The night cools off the depths of the dream and feels the nightmare, like a spirit at the window, perched between two minds, placed there within all that is this dream.

MAMOTH: Andrei Tarkovsky has said that our times are characterized by the loss of rituals. I have found a ritual of faith in your paintings; how do you make it way back to mankind of our time through painting?

A. FOGO: I look at rituals as archetypal foundations of contemporary culture. Since the beginning of time, human beings have always needed answers to existential questions and dialogue with supernatural, invisible entities, which have had and still have so many names: God, cosmos, superior entity, and so many more, depending on one’s origin, beliefs, and cultural background. All of these expressions and related traditions and customs share the same roots, as they are acts of faith. Even if these lack fundamental proof and truth, human beings believe. I think that engaging with paintings, and art more broadly, is an act of faith, too, and an innate human need.

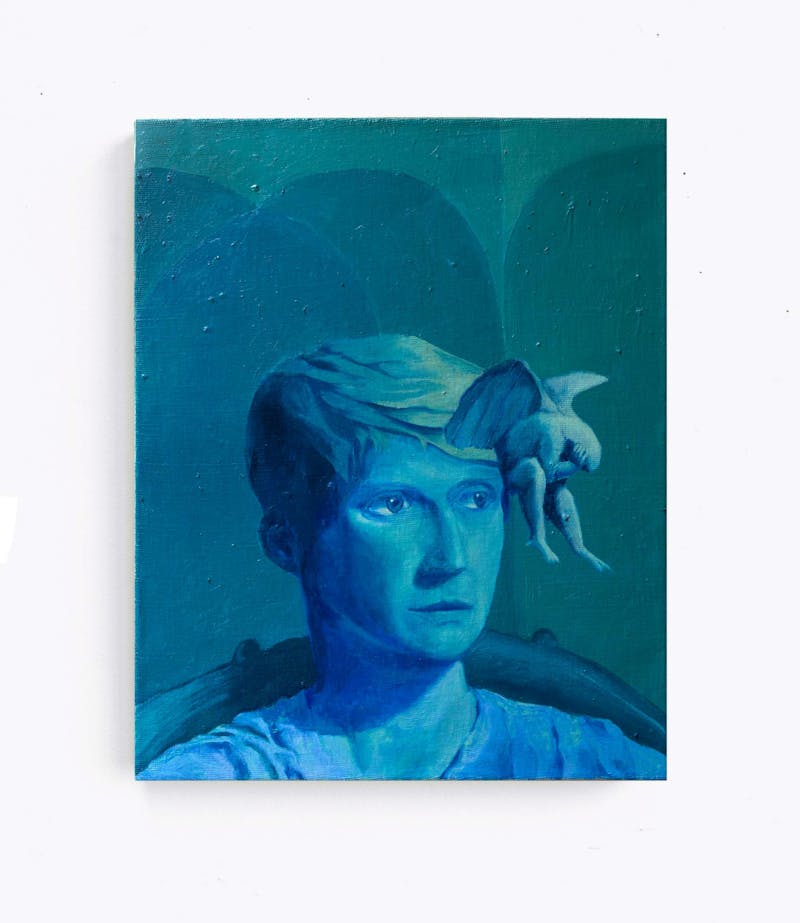

MAMOTH: What is your explanation of Nocturnal (bad dream)?

A. FOGO: Nocturnal (Bad Dream) is a moment suspended during the night. An intimate moment between two “animal” figures resting, dreaming. There’s also a small winged figure recalling the devils of Giotto. It is a link with another dimension.

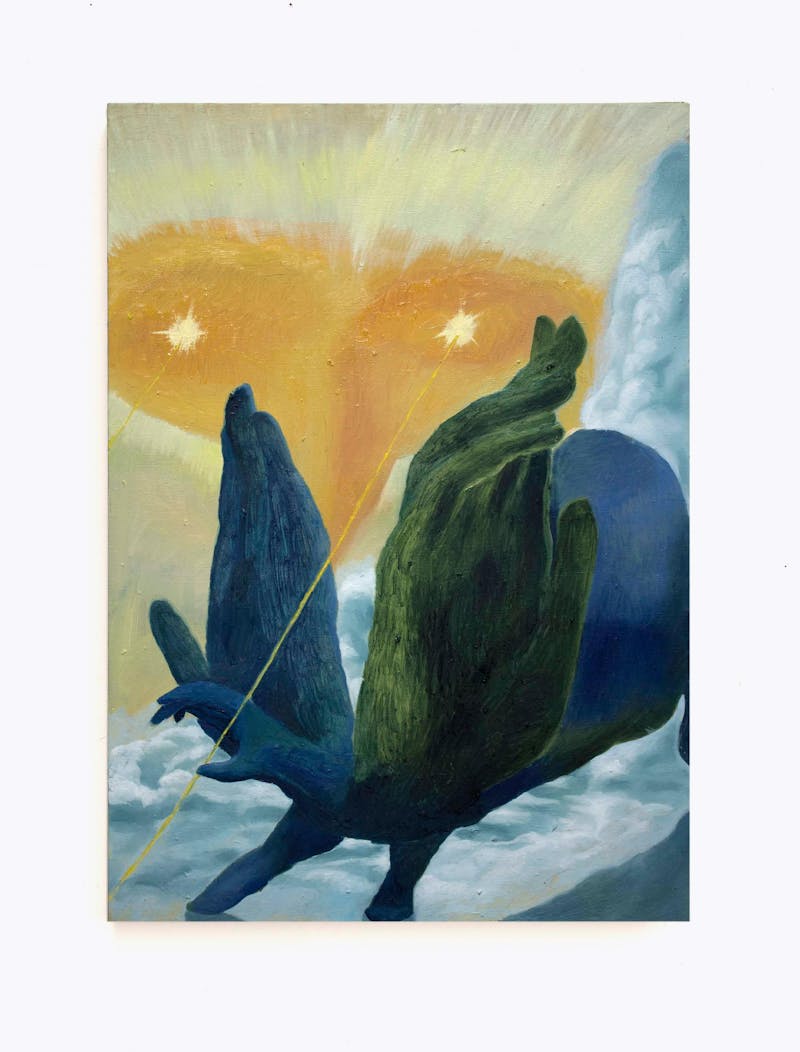

The spirit with its wings outstretched is Fogo’s The Devil of Giotto, the image of a devil painted by Giotto, the founder of the Italian Renaissance, on a fresco in the Basilica of Saint Francis of Assissi: a prominent aquiline nose, black horns on its smooth swollen head, a sly smile, hidden in the clouds at the top of the fresco. The spirit of Renaissance painting is found in the confession of life and the conversion of divinities. In the face of religious and cultural imagination, Fogo creates a new semantic meaning for Giotto's demon, and in so doing reveals an independent and objective spirit, which is the most intimate expression of the human mind.

The sun illuminates the clouds on high. The fingertips extend straight towards the other side of the traversed clouds. Facing the novelty of the world’s eternity, all is already and entirely known. The hand is the angelic messenger of nature, of nature’s countless creations, its boundlessness, yet none for itself- only possessed in its pursuit.

MAMOTH: You have studied painting in Venice, where Biennale, operas, and old Venetian masters unfold. What did you explore most when living there?

A. FOGO: It was really inspiring every year seeing the contemporary art world colliding with a city like Venice, very baroque and rich in terms of the history of art. I think also that my fascination for holy objects and relics started there, visiting all the churches in the city. There are 148 churches on the island. Every one of them has at least a little treasure inside. Incredible.

MAMOTH: Could you explain the title of Acchiappasole?

A. FOGO: Acchiappasole is a funny way of trying to catch the sunrays. It is an attempt of taking physical possession of something that we only experience.

Great Apollo, the sun god of Greek mythology, is placed a totem of faith that has been turned upside-down. By means of a new image, the artist constitutes a living place for the spirit of God.

MAMOTH: Your paintings often depict mythological scenes and so there will be a cross-culture dialogue between your works and their eastern audience. Could you tell us about Apollo’s Perversion and Bruciaspiriti?

A. FOGO: Apollo is the Greek divinity related to the sun; his task is to make it rise every day. I depicted him, or better to say his feet, during the night. I imagined the night as a moment of transgressions that don’t belong to him and his myth.

Bruciaspiriti depicts a moment during the day where there’s no sunlight anymore but it is not already night-time. Things don’t have a shadow at that moment, it is pretty much all in the same tone, that’s where the blue comes from. And the fact of the shadow allows me to introduce presences that are not properly real. I like to think that a spirit has more or less the same weight, volume or presence as an existing thing in that particular moment. The scene in its totality is a summoning of that instant.

When the day and night meet, when light and concealment pass through hand and place, there is no need of eyes to see, to believe. In the midst of nothingness, any object or soul has the selfsame weight. It is within the dialectic of mysticism and existentialism that Fogo's works are perfectly explained.

Bruciaspiriti, 2020, oil on linen, 180 × 200 cm © MAMOTH

Bruciaspiriti, 2020, oil on linen, 180 × 200 cm © MAMOTH

A. FOGO: Blue, as I explained in the answer before, comes from a particular moment of the day that I like for its ambiguity. In general, I am interested in working with the semantics of objects. I am fascinated by how much an object can really tell us about its history and function. Objects, even if removed from their original contexts, often maintain some sort of definite aura, but they become ambiguous, religious and sacred objects especially. There is a huge potential for new narratives to be born from objects such as these. As human beings, we attach such strong meaning and power to symbols, but if we forget for a moment our cultural background, we see things, objects, as empty, meaningless containers.

Fogo lives in the Adriatic town of San Benedetto del Tronto. His studio houses his collection of artefacts from different ancient civilizations: bird specimens, ceramic figures of the birth of Jesus, a Native American hand-cut silhouette from the Woodland period. These ancient stories that walk with time will be preserved forever. Just as you can see all of everything, and different from all of everything.

Alessandro Fogo’s studio in Marche

MAMOTH: Thinking back to MAMOTH’s first group show last month, how did you feel about coming to London and attending MAMOTH’s exhibition opening?

A. FOGO: I always had a particular fascination for London, especially for its painting history. I remember a lot of great painting shows that I saw there, so to me it’s an honour to have the chance to show my work in such an environment and also I was happy and glad to show alongside artists that I admire.

MAMOTH: What are you working on during the quarantine time?

A. FOGO: I am dedicating part of my time to renovate the house where I live and my studio. I think this is a moment where I can really focus on my thoughts and raise self-awareness about myself, my routine, and my work and how to improve and evolve as a human being also. So I am reading and thinking a lot about new works and what will happen next. These are my solutions to avoid anxiety.

Alessandro Fogo (b. 1992, Thiene, Italy) lives and works in Marche, Italy. Fogo sources imagery like an archaeologist digging for artefacts, often drawing on ancient historical and alchemical motifs, which are then layered and interspersed with familiar everyday objects. Fogo was the 2019 winner of the Premio Combat painting prize in Italy and recently exhibited at Galleria Continua.