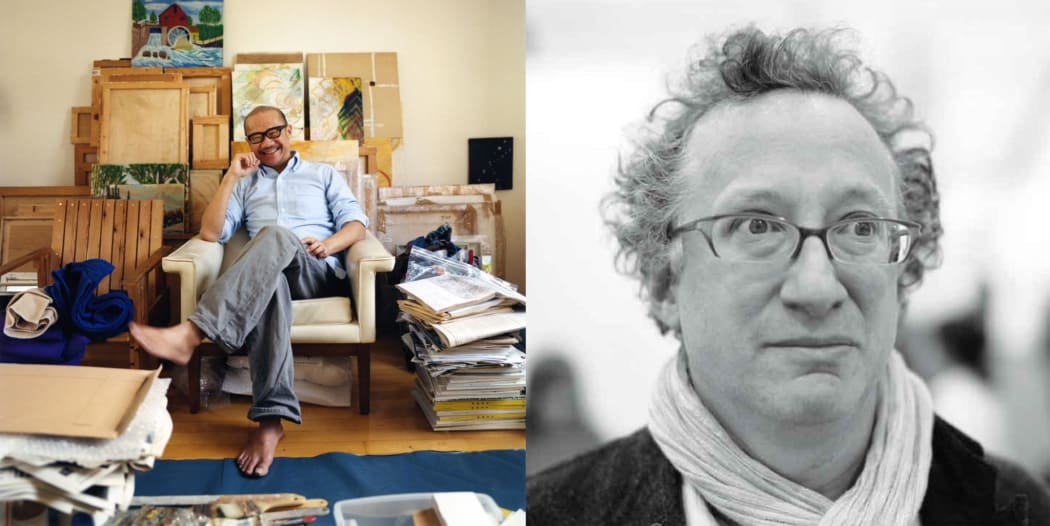

MAMOTH were delighted to invite Barry Schwabsky to speak with one of our artists, Sherman Sam about his latest duo exhibition 'Duet' with Nancy Shaver. The exhibition runs from the 18th of January to the 29th of February 2024.

Barry Schwabsky is a writer, critic and poet. He is the current editor-at-large for Brooklyn Rail and has written for various platforms including Artforum, London Review of Books and Art in America. He has written many books on such artists as Henri Matisse and Alex Katz and has taught at several universities: Goldsmiths College, New York University and Yale to name a few. He currently lives and works in New York, USA.

Sherman Sam (b.1966) is an artist and critic based in London and Singapore. As an artist, he has shown with various galleries and institutions such as the Centro de Arte, San Joao de Madeira, Portugal and the Rubicon Gallery in Dublin, Ireland. As a writer, he contributes regularly to platforms such as Artforum, Ocula and artcritical.com. In 2006-2008 he was the Inspire Curatorial Fellow at the Hayward Gallery in London and was the selector for the Pro Arts 2010 Juried Annual in Oakland, California.

Click here to find out more about the exhibition 'Duet' with Nancy Shaver and Sherman Sam., in the meantime please enjoy the interview.

In Conversation - Sherman Sam with Barry Schwabsky

Longtime readers of the Brooklyn Rail will remember the insightful critical contributions Sherman Sam regularly made from London-and occasionally from elsewhere: Dublin, Porto, his native Singapore-between 2006 and 2011. But they may not know his remarkable paintings, which have rarely been seen in the US. Luckily for me, I got to know them-and him-well during the ten years I lived in London. While preparing to write the essay for the catalogue for Sam's current exhibition at Mamoth Contemporary, London, alongside Nancy Shaver (on view through February 29), we had a Zoom conversation of an unusual sort. With the artist in Singapore and his paintings in his London studio, he arranged for his good friend and fellow painter Clive Hodgson to show me the paintings while we talked. So the conversation encompassed not only three time voices but , three time zones: nighttime in Singapore, morning in New York, evening in London. It was only the fading light at nightfall in London that made the paintings hard to see that brought our conversation to a close.

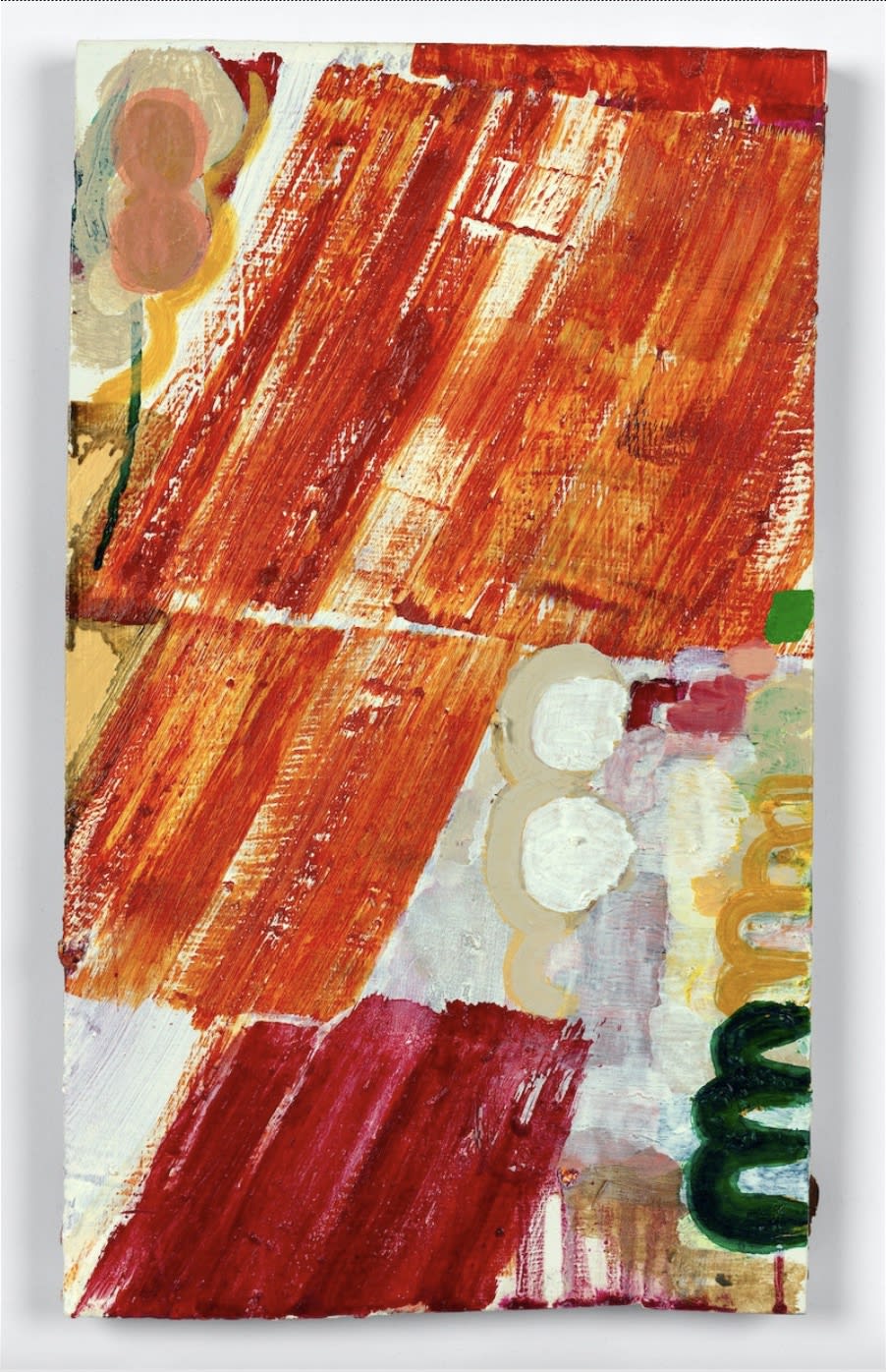

Sherman Sam, Heaven must be, 2022. Oil on panel, 11 1/3 x 6 1/4 inches. Courtesy the artist and MAMOTH. Photo: Todd-White Art Photography

Barry Schwabsky (Rail): So what we're going to see here are all paintings for the show?

Sherman Sam: We're thinking of hanging about four or five of my paintings in the show. The painting on the right is called Heaven Must Be, and the painting on the left is called Badia.

Rail: That title, Badia, what does that mean?

Sam: It's from a song. I think it's Earth, Wind and Fire. It's called September.

Rail: Taking a title from songs is something that you've done some decades now.

Sam: Yes. I like found, found titles. I mean, all these singers, they write much better titles than I do. Also, they come with a history. I like the readymade nature of song lyrics.

Rail: On the screen, I feel like I'm seeing everything at an angle-seeing the edges of the paintings. And they have an edge!

Sam: The woodwork is always really poor, I know. The joinery isn't perfect. I asked someone once whether I should fill in the gaps between the right angles. And he said, eventually the filling will just pop off anyway. So I've left the gaps.

Rail: Are they all quite recent? You used to spend a long time on some paintings, do you still do that?

Sam: The two you saw, and this one, TITLE, their time frame is probably about three to four years. So they're quick paintings for me. The fastest painting I've ever painted took a year, I think.

Clive Hodgson: And you think that there's long time makes them better?

Sam: I don't know. You'd have to tell me. You live with three of my paintings.

Rail: What takes you so long?

Sam I don't know what I'm doing?

Rail: That should make it faster!

Sam: I think I'm indecisive, or I'm open to so many possibilities. It makes me take pause. What I say to people is sometimes, when you're a painter, the thing you have in your mind inhibits you from seeing what your hand has just done. So I take a while, I pause, to get used to what I've done. Very often you think, Oh, I need to paint this yellow line here. And the yellow line you paint is not the yellow line in your mind. So it takes a while to see what you've done and the possibilities of what can follow. New possibilities following the balls-up.

Rail: Well, it's not that there's a mistake. You've created a new situation that you need to respond to as it is, not as you imagined it would be. But then how long does it take you typically to come to the point where you can make the next move?

Sam: It depends on the painting, but typically the next move doesn't happen straight away. It can be weeks, months. I have a painting in my studio that's sat there, I think for at least five or ten years and I've only touched it about three times. I know which way up it is and I think I must touch it one or two more times to complete it, but I have no idea what I want to paint on it.

One day I'll paint something on another painting and I'll realize that it will help me realize what I need to do on that painting.

Rail: And so all these paintings that you have at various stages of work, do you tend to have them all up on a wall at the same time? Or do you put them away, so that you have to deliberately take them out and put them up in order to start to notice what you might do?

Sam: At any one time, I think there are about ten paintings I'm looking at, but there are thirty to forty paintings that are in process. So some paintings disappear from my vision, like the one I was just mentioning that's still in progress. That's usually not out. It's just behind, it's three paintings behind in the stack. I mean, I do admit that I think my studio is slightly smaller than it should be. I've outgrown it.

Sherman Sam, Ba-dee-ya, 2022. Oil on panel, 14 1/2 x 8 1/2 inches. Courtesy the artist and MAMOTH. Photo: Todd-White Art Photography

The two paintings you saw previously were from 2022 and the painting on the left is also from 2022 and it's called Gotta Move On, Gotta Move On. And the painting on the right is called Disco Inferno and it's from 2021.

Rail: But, just to be clear, when you say it's from 2021, that means…

Sam: It was finished in 2021. The date that's on the painting is the finish date.

Rail: So you're not one of those people who has, say, 2018-2021 as a date. You're not showing off how long you spent on it.

Sam: Also, I can't remember when I started them. And, and sometimes I think if you put it away for ten years and you don't see it for ten years, I'm not sure what that means.

Rail: You know that Matisse painting French Window at Collioure that's in the Museum of Modern Art, that one that's an almost all-black rectangle? That's his most abstract painting. The museum dates it 1914, but never left his studio. To me it's not clear that he ever really decided that it was finished. I think in that sense, he kept it in a state of potentiality for forty years.

So here's a morbid question: If you were to die today, all those paintings that are in your studio that you don't consider finished, how would you feel prospectively about them being shown and people acting as if they were finished?

Sam: Well, I'd be dead. But actually, what I've told my potential executor is if he thinks it's a burden to deal with some of these things, he should just take them out into a field and torch the lot.

But I think I'd like to see them in the world, the unfinished stuff, and looking down, be very amused by what people make of it in relation to all the stuff that's finished. Maybe they can't tell the difference. Maybe you can't. I usually can't. I mean, I only make the things. You think I know what I'm doing?

I like to think that when it leaves my studio, I can live with it, but there have been, I think, three paintings that have been out, left the studio, come back, and I thought, Oh, I know how to finish it now.

Hodgson: Should I change them?

Rail: Yeah, go ahead.

Hodgson: By the way, Sam, do I get paid for this?

Sam: Maybe. I'm thinking about it. Depends on how good a job you do.

The one on the right is called Ça Plane Pour Moi. And that's from 2020. And the one on the left is from 2019 and it's Too Long To Stop Now. And it's dedicated to Tom.

In that one, gravity is working the right way. In a lot of them, gravity is working the wrong way.

Rail: And that's because you've changed the orientation in the course of work or? I remember in the 1990s there was a big thing for painters in New York to have very deliberate drips going wrong ways.

Hodgson: You could put them sideways, in landscape format, if you really want to be radical.

Sam: That's a good point. I don't paint in a landscape format.

Hodgson: Can you say something about repetition? You have repeated motifs, like a typewriter printing the same key, the same letter, bang, bang, bang. A staple gun, bang, bang, bang.

Sam: Inability to get it right the first time round, so gotta do it again.

Rail: Are you talking about repetition from one painting to the other or within a painting?

Sherman Sam, Gotta move on, Gotta move on, 2022. Oil on panel, 15 1/4 x 9 3/4 inches. Courtesy the artist and MAMOTH. Photo: Todd-White Art Photography

Hodgson: Within a painting. You know, you've got three coat hangers in this one.

Sam: Elbows.

Rail: Ah, elbows. Okay.

Hodgson: You tend not to make bigger areas, you make repetitions to get across the canvas, or the board, as we should say.

Rail: To make a bigger area. Even when putting it into a bigger zone, you seem to always want to kind of keep the individual mark identifiable.

Sam: Yes, I like to keep the mark there. I guess I could get a bigger brush. There have been, I think in the later paintings, slightly bigger brushes. I think the real reason that it's always a small brush is they're easier to clean. I don't like these big brushes sitting around in the turpentine.

With representation, there can be increase and decrease in the scale of things. There's some kind of perspective that occurs. That's another question, about the depth in them. So the repetition often seems to have to do with changing the size of the motif. Well, something's got to happen in the painting. Otherwise, it's just a big, flat rectangle with brushstrokes.

Rail: Some people like that.

Sam: I don't know why, but after I said that, immediately what popped into my mind was Soulages.

But it's almost like motion. Something is moving. Someone once said to me, what he thought of my drawings was, it was like thinking.

Rail: Yeah, but what, which kind of thinking? Seriously, there are all kinds of thinking.

Sam: It's a very slow ADHD.

Rail: So it's a mind racing very slowly.

Sam: Yes. It's a mind thinking that it needs to race very slowly.

The one on the left was in my studio for a long time. I finished it in 2022 and it's called Play that Funky Music. I title them after I finish them. Usually what happens is I play music. In this particular period, I wanted to have disco music titles. And why was that? I don't know. It was just some stupid idea that disco is funky.

Rail: That's a kind of nostalgic thing, isn't it? It refers back to such a long-ago period.

Sam: Different groups have different references. Like one when Lou Reed had just died, I was playing Lou Reed. So there's a lot of Lou Reed lyrics in the titles of a certain period.

The painting on the left, it did sit in my studio for a long time. I couldn't figure out how to make it work. So many things happened to it along the way.

Rail: And just out of curiosity, can you recall now what, what allowed you to finally finish, what were the last things that you did that satisfied you that it was done?

Sam: I think it was the, the splattering on the right, the sort of Indian yellow splatterings on the right.

And the painting on the right is from 2018 and it's called still haven't found. This is a painting that also sat in the studio for quite a long time. I cut a bit of it off it, or it might be an offcut of a painting. That's it. I think it may have been a top slice cut off and turned on its side.

Rail: Is that something that happens much, that you actually cut pieces off?

Sam: Not very often, but there are three or four paintings that are like that, where I've cut a bit off. I think in the case of this painting, this is the bit that I didn't want, and somehow I made it work.

The paintings over time have gotten taller and taller. I stopped getting used to the squatter format. So in some of the older paintings, I just thought, what the hell? And I just took a bit of it off.

Rail: And do you ever add a piece to the surface?

Sam: No, it seems a lot of work. But I wouldn't say no to maybe rejoining what had been the parts of a painting.

Rail: Rejoining? Meaning you'd cut a piece off a painting and then you would put the same piece back to the same painting?

Sam: Well, it would be a healing gesture.

Rail: Now, in a way this sort of goes to what Hodgson was saying before about seeing certain things as noses or hangers and you said, no, they're not hangers, they're elbows. So for instance, in the painting on the right, the blue thing, you know, it's hard not to see a stairway. And you know, those kinds of associations seem kind of unavoidable with some of these things. But then, even if they're unavoidable, are they significant or are they kind of random?

Sam: They're random. I like them though, because I like the fact that you can look at them and all these things drop into your brain. I think we can't help ourselves. We see these things, which is why they're not square gray paintings or just one rectangle sitting on top of another rectangle.

You know, I try not to have eyeballs and noses in there. You know, if you see it, you see it. But if I see it while I'm working on it, I'll paint it out.

Rail: They're pretty hard to actually eliminate, I suppose. Because any kind of simple shape can be translated into, you know, a hanger or an elbow or, or whatever.

Sam: Well, with the painting on the right, the steps-when I see it now it makes me think of a kitchen towel! You know, you have these white kitchen towels with the blue frame on the edge?

Rail: Clive is in the dark now.

Hodgson: The light is fading fast here. There's not much lighting inside.

Sam: This is true.

Rail: That that's an interesting thing in itself, that you don't have much artificial lighting in your studio.

Sam: No, and I tend to paint at night as well. I'm sometimes when I paint with a lot of yellow, I have to look at them in the day. I look in the day. And I paint in the night.

Rail: So you there's a certain amount of, not exactly blindness, but a sort of dimming of what can be seen that creates the atmosphere in which you do things.

Sam: I always call it luck, but I think you get used to the dimness.

Rail: Like looking at an Ad Reinhardt painting. It takes a while to get used to all the black and then seeing the different blacks emerge and recede.

Sam: We should ask Clive. Clive has the real life experience. Are you starting to see more of those paintings now?

Hodgson: What you see in artificial light is that they've got a shiny surface. Shiny and matte begin to show as you move past the painting, more so than during the daytime. They're quite rich in medium. What is the medium that you put in to make them shiny?

Sam: I don't do it deliberately. I use the medium to make the paint runny, but the more I use, the more I paint on it ,the more medium gets on it. But it's just a store bought medium.

Hodgson: You could choose to use white spirit, but you choose a store bought medium.

Sam: Yes, I guess I could, but if you use white spirit, it'll just dry out and make your paint chalky.

Hodgson: So you like the jammy, transparent gloss.

Sam: Well, if I'm going to keep working it on for ten years, I figure jammy, transparent gloss might be better than white spirit that might just dry out and fall off.

Hodgson: Yeah, but it's seductive, you know. With the kind of resonance in the color that that would otherwise not be.

Sam: I guess it's not that conscious. It's more to do with just making the paint work for me rather than the surface being… I mean, I do like that the surface is uneven and they are dry patches and wet patches or shiny patches and matte patches, but I treat that as byproduct rather than deliberate.

Sherman Sam, Too long to stop now (For Tom), 2019. Oil on panel, 16 1/4 x 16 inches. Courtesy the artist and MAMOTH. Photo: Todd-White Art Photography

Hodgson: I don't want to interrupt because it's really Barry's talk, but I wonder, do you think our perception of painting has been affected by looking at screens all the time? Nowadays people are looking at bright images on an iPhone all the time. If you look at an oil painting, in comparison, it's a relatively dull experience. Does that oblige us, to some extent, to try to make something which is more active or more colorful or something?

Sam: I don't know. I'm skeptical of that idea. When you're looking at a thing in real space, in real light, you're not really looking to see it the way you see things on a screen, but what I do think is that people, younger people, make paintings that will look good on the screen. And maybe they don't look as good in real life as they would have if they didn't look so good on the screen. Their main way of being appreciated is almost to get likes on Instagram. I don't think it affects how we see actual paintings, but it affects how people make paintings sometimes.

This kind of thing has been happening for a long time. I remember thinking about artists like David Salle and Julian Schnabel, that the paintings they made almost always look better in their catalogues than when you actually looked at the paintings. They were somehow slightly duller.

Rail: Instagram is taking that process further. Maybe it didn't even start with photography. It maybe started with the invention of the electric light, you know?

Hodgson: If you think of the circumstances in which Rembrandt was working. Those houses were amazingly dark in Amsterdam. Small windows and candlelight.

Sam: That's why his paintings were dark?

Hodgson: I don't think it is why they're dark, but I think it was a kind of general atmosphere that was so familiar to him.

Sam: Well, also those medieval paintings….

Hodgson: …are very bright in color.

Installation view: Duet, MAMOTH, London, 2024. Courtesy MAMOTH

Sam: But you could only see them in candlelight. How many more paintings do we have left?

Hodgson: You've seen all of them now.

Sam: Was that eight paintings? For some reason, I thought there would be one or two more but never mind.

Rail: Well, if there were I wouldn't be able to really see them anymore anyway. It's amazing how different the light is after fifteen minutes.

Hodgson: Yeah, now it's gone.

Rail: So when you're painting in a low-light situation like this, Sherman-and this is a serious question-are you always sure what color you're putting on the painting?

Sam: Pretty much. When I paint yellow on yellow, yellow next to yellow, it's a bit harder because all the light in the studio's yellow.

Hodgson: It's not immensely bright, Barry, I can tell you though.

Rail: Sherman, what do you have to say about your paintings that we're not saying?

Sam: I think I'm a lot better at answering a question than having a narrative or a spiel. So shall I tell you how I make them? How I start is I cut the panel down to size first. Usually it's a response to what happened before, so they've been getting bigger. And then I decided I was going to make a whole bunch of smaller panels. Also, sometimes they are squarer and other times they're taller. In the summer when I manufacture them, that's a response to what's been going on in the studio.

Rail: Why do you make the panels in the summer?

Sam: I like to saw wood with the windows open and I can prime it with the windows open.

Rail: I assume you also paint in the summer.

Sam: Yes, I do. It's all an ongoing process. But then I might make it one summer, but it might be three summers later before I start painting on it.

Rail: So the prepared panel, is that in your mind already a painting that you're working on or does it really start when you put the first paint on?

Sam: The working on the painting starts when I put the first paint on, but sometimes I look at the panels for a long time. And feel very pleased with myself because I always think it's an accomplishment getting that far. I also in each group of paintings, I start with a series of marks. That's how I set the ball rolling. And sometimes how they start leads me to think about some of the older paintings.

Rail: What I'm hearing from you is that it doesn't start with a single mark. It either starts with a group of marks or else some kind of gesture that you don't experience as a kind of single object.

Sam: Yes, I think that's right.

Rail: Meaning that at a given time you're likely to make similar sorts of moves on one painting after the other.

Installation view: Duet, MAMOTH, London, 2024. Courtesy MAMOTH

Sam: It worked in one painting. Why not? Try on another. But that's also how I find, I don't want to say the word "solution," but I do it on one painting and I suddenly think oh, I can put it in there.

Rail: That's very interesting. It creates a sense of a chain, gives you continuity while allowing you to produce new things.

Hodgson: To some extent what you're describing is about not knowing what you're doing as a way of making things progress.

Sam: I don't have a plan. I don't know how they'll end up. I don't think I really have a system.

Hodgson: You don't know what you want in a painting. If you did, you could get other people to do bits but you want it to be you that's doing this unknowing thing.

Sam: I wouldn't even want people to manufacture my panels anymore.

Rail: That's an interesting thought, the idea that something that's known is inherently reproducible by anyone. But if you say you don't know what it is, then in a certain sense you've got a secret that you keep to yourself by even keeping it secret from yourself. And therefore no one else can do it.

Sam: But one thing I've decided: it's a painting. We've got to go with paint.

Rail: Well, not everybody does. People put a lot of other stuff on paintings. Apollinaire already said so around 1913 in The Cubist Painters.

Sam: Did he actually talk about painting with stuff?

Rail: It's here: "You may paint with whatever material you please, with pipes, postage stamps, postcards or playing cards, candelabra, pieces of oil cloth, collars, wallpaper, newspapers." But you don't go for any of that. I get it.

Sam: Because that lets the world into the painting. Once you do that, once you stick some bit of the real world into it, you can stick any bit of the world into it.

Rail: And that's just too much?

Sam: That's just too much stuff to have to sort out, to decide about. You know, it could be a baby shoe. It could be a chair. It could be a whole house it. Once you start thinking about it.

Hodgson: Sherman, can I ask you a question about the way you make marks? I think it's quite slow in a way. I'm comparing it to the way that I make marks which is quite flicky and kind of calligraphic, I suppose. The way that you make marks seems slow and deliberate. Can you say anything about the marks you'd make? When you're painting, does your hand move fast or slow?

Sam: It varies. I don't think it moves very slowly.

Hodgson: But you don't want them to look too gestural.

Sam: They're not. They're not meant to be in and of themselves, expressive. They're closer to constructive than they are to expressive. But I just think of them as the marks I'm making. When I was a student I was much more expressive than I am now. I do think it has to do with the fact that I draw a lot too. I think sometimes the way I move my brush is like the way I move the pencil.

Installation view: Duet, MAMOTH, London, 2024. Courtesy MAMOTH

Hodgson: So a felt tip pen would work.

Rail: No, no, no, no.

Sam: It it's a joke Clive always plays on me. he keeps telling me I should draw with a felt tip.

Rail: Well, have you ever tried it?

Sam: No, it's too permanent. Erasing would be a lot of work.

Rail: I see. So you do a lot of erasing in your drawings?

Sam: Yes, yes. I used to do a lot of painting out in my paintings as well, but I think I paint out less now. Just sort of painting around maybe.

Rail: When you say painting out that that means covering over?

Sam: So, like the painting of mine that you own? That was painted out many times and painted in. I think there's a lot less of that type of activity now. So in general I think that, although they might take a long time, there's less painting action going on. The waiting has to do with trying to figure out the mark I need to make without having to do too much correction.

Rail: And do you ever change your mind about a painting being finished?

Sam: I try not to change my mind once I let them out of my studio. But when I think a painting is done, I put it away. I show it to people and then I put it away and just sit on it for a little.

Hodgson: It's unnerving if a painting leaves your studio and you see it in somebody else's house or something and your heart sinks. That's a bad feeling.

Sam: I agree, but it's rare.